Why do coins have serrations (or grooves) around their edges?

To understand why many coins have edge serrations we must go back to a time before coin making-machinery was available.

From the first millennium BC, when coins were invented, up to the 17th century (roughly), coins were hand hammered by skilled artisans. The process involved placing a blank piece of metal between two engraved punches and hammering the top punch several times to imprint images on both sides.

Medal portraying a 15th century engraving of a moneyer’s workshop.

Because the metal splayed out under pressure from the hammer strikes, early coins lacked a uniform edge. Even when coins were pressed into metal sheets and then cut out, the results were far from perfect.

In an era when gold and silver pieces were in circulation, this characteristic made them vulnerable to ‘clipping’ - the act of illegally filing or shaving off a small amount of precious metal for profit.

Remember, back then the value of coins were tied to their weight in precious metals. As a result, ‘heavy’ coins tended to be hoarded, leaving only the clipped coins in circulation. (Believe it or not, there’s a law for this phenomenon. It’s called Gresham’s law and it states “bad money drives out good”.)

Sometimes clippings were mixed with base metals and used to create counterfeits, another extremely pressing issue of the age. Even the most severe punishments, including the death penalty, appeared powerless to stop these criminal activities.

Milled coins

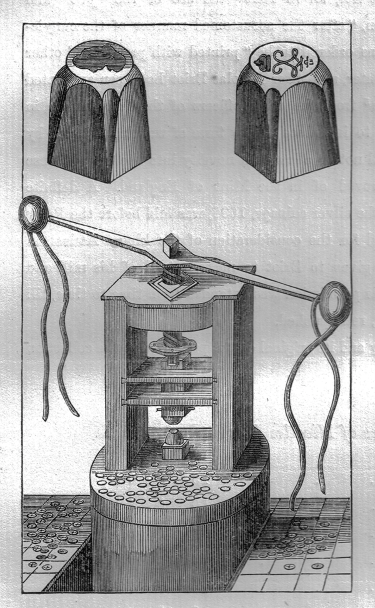

The development of ‘milled’ coinage enabled monetary authorities to hit back. Milled coins took their name from improved rolling mills capable of making consistently thick sheets of metal for blanks. But they are also strongly associated with the employment of the screw press in coin making.

Essentially, the screw press worked like a Roman olive or grape press. The die was pressed into the blank by means of a screw originally turned by mint workers, and ultimately by steam-power. The appearance of the resulting coins represented a marked improvement on their hammered predecessors.

A Mill for Minting Coins, by Rosser 1954 at English Wikipedia (Original text: Rosser1954 – Roger Griffith) R.W. Cochran-Patrick, Records of the Coinage of Scotland. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Milling_of_coins.jpg

Playing no lesser part in the battle against clippers was the coin collar. A hardened ring with an aperture fractionally larger than the die, the collar surrounded the blank to prevent the outward flow of metal during the striking process.

Swiss-born Jean-Pierre Droz (1746 - 1823) is said to be the first person to have realised that the collar could be used as a third die. He developed a collar comprising six segments, each with raised lettering on its inner wall, which pressed against the edge of the blank as it was struck.

Decorated edges effectively stamped out clipping and counterfeiting. With these features coins were far harder to fake and easier to spot when clipped.

Harking back to the earlier era, edge-lettering is one method that can be observed on modern coinage. More familiar, however, is the serrated edge, or reeded edge as it is known in the United States. On a modern coin press, a serrated collar imparts these grooves into the struck piece.

Note the different styles of interrupted edge serrations on $2 and $1 coins.

Today, the use of serrations is more of a tradition than a necessity. Often they are continuous (as on 20, 10c and 5c coins), but you’ll also find examples of interrupted serrations, such as those on our $2 and $1 coins. Apart from the fact they look neat, these adornments are also said to fulfill a useful function on behalf of blind and visually impaired people, helping them to distinguish different coin denominations.